Pressure cooking appears simple enough: put in liquid and food; seal valve; set pressure to high or low; set time; walk away. Right? Whether you answer yes or no, this article on Pressure Cooking 101 is for you!

I bet some of you are shaking your head back and forth and yelling, "No, it isn't simple at all!" While others are saying, "Yep, it's easy."

What if I tell you that both of these statements are very true? It is easy, but it isn't simple. In this article, I am going to go over the history of pressure cooking, the principles behind pressure cooking, what type of cooking containers work best, and how to adapt your favorite recipes for the pressure cooker.

Before we get started on pressure cooking 101; if you are new to the Ninja Foodi, you might want to read this article first: How to Use the Ninja Foodi

If you prefer to learn all about pressure cooking and the Ninja Foodi through video lessons, then the Ninja Foodi Pressure Cooker & Air Crisper Online Course is for you! In this course, I go over each and every detail about using the Ninja Foodi so that you can use it to its full potential.

By the end of this article you will have a much better understanding of how the pressure cooker cooks your food and you will be able to apply this knowledge to make better food more consistently. So, stick around through the super boring stuff the payoff is tremendous!

Have you ever read a statement like the one above and then taken your time to read an article that; never answers your question, is full of fluff, doesn't give practical examples, and leaves you feeling like you just wasted your time? I have and I don't like it. I can promise you this article is not like that. I have spent more than 40 hours of research and doing my own testing to write this article. If by the end of the article, you still have a question that I didn't address, I want to hear from you! Leave a comment or send me an email. Nothing gives me more pleasure than helping people with cooking!

By gaining an understanding (in plain English, I promise) of pressure cooking, you will be able to better determine what foods to pressure cook and for how long. I'm excited to be writing this because I know I will be learning tons of quality information right along with you.

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase after clicking a link, I may earn a small commission. Thank you for your support!

History of Pressure Cooking

Pressure cooking has been around since the late 1600's, but didn't become popular until the early to mid 1900's when it was determined by the US Department of Agriculture that pressure canning was the only safe way to preserve low-acid foods. It wasn't until 1938 that the first pressure cooker was made in the USA for home use. It is important to note that electric pressure cookers which I am focusing on in this article do not reach high enough temperatures for canning low-acid foods.

These, first generation pressure cookers looked like a pot with a lid and had a weight valve that jiggled while it was cooking. This weighted valve was the old version of the red button valve on the Ninja Foodi. You would add liquid and food (meat mostly) to the "pot," cover with the lid and heat it on the stove. As the liquid boiled inside the pot, steam was produced. The steam built pressure in the pot that would cause the weighted "jiggler" valve to jiggle and trap the steam pressure in the pot. From what I have read, these old models did release some steam during pressure cooking and the pot was not a sealed pot like we use today.

The second generation pressure cookers switched over to a more proprietary spring loaded valve and usually had two or more pressure settings. There were some safety features built into the second generation pressure cookers, but not like we have today. There was a gauge that showed the operator what the pressure level was and if the heat source was not reduced when the pressure reached it's max, steam would be released automatically.

Fast forward into the 1990's and the third generation of pressure cookers were born. The electric pressure cooker. These had more safety features built in and they continued to advance as technology advanced to bring us what we are using using today. A programmable electric pressure cooker with smart technology. Despite all these advances the principles remain the same with pressure cooking and I'm going to get into that next.

Principles of Pressure Cooking

Even if you have been pressure cooking forever and a day, you might learn something in this section. I know I did. The basic principles of pressure cooking are pretty straightforward, but I think it's important to delve a little deeper. Once you gain a better understanding of the principles of pressure cooking, you will be able to modify recipes and even create your own recipes with better and more consistent results.

Principle One: The boiling point of water

Traditional stove top cooking: When you put a pot of water on the stove and turn it to high, the pan is heated which transfers heat to the water. The better the pan is at conducting this heat to the water, the faster your water will boil. At sea level (I will discuss how altitude affects the boiling point a little later) when the water temperature reaches 212° F, the water will boil. You know when you see those little bubbles rising up through the water and hitting the surface? That is because the water on the bottom of the pot has reached its boiling point and those bubbles are the vapor/steam (formed by the water molecules breaking apart) making their way to the surface and they evaporate into the air.

Because the heat source is at the bottom of the pot, the water closest to the heat source reaches the boiling point first. As the water is heated to the boiling point closer to the surface, you see what we call a rolling boil. This means the water in the pot has reached 212° F and all those bubbles are steam being formed that break through the surface and escape into the air. So, as a general rule, you cannot heat water past the boiling point on a stove top because it evaporates before it can get any hotter.

The boiling process is slowed down when you add food to the pot of water because the food is absorbing heat from the water, but the water will eventually boil if enough heat is applied to the pot. This boiling water continues to transfer heat to the food and thereby cooking it.

Let's use potatoes as an example here. You place a pan of water on the stove, add in your potatoes and turn the heat on high. The water starts to boil and the potatoes begin to cook. There really isn't anything you can do to speed up that process, right? I'm sure some would say, you can put a lid on the pot. Yes, you can. And that can help bring the pot of water to the boiling temperature faster, but once it hits a boil it does not get hotter even with the lid on, so it does not cook the potatoes faster. Have you ever had a covered pot of boiling water on the stove and the lid bounces around? That is the steam forcing its way out.

Another thing to note while we are on this subject, is how starchy foods tend to boil over especially when covered. This happens because the starch in the food increases the surface tension of the water. So, all those steam bubbles that are forming can't escape through the surface easily like they can with plain water. The bubbles form a foam and require more force to burst. Since they aren't bursting as fast, they build up and eventually boil over.

Principle Two: How altitude and psi affects the boiling point of water

These are all approximations, there are numerous factors that can change these numbers, but this will give you the general idea.

This can get confusing, so I am going to try to explain it the best way I can. Remember earlier when I talked about the boiling point of water at sea level is 212° F? This happens because water boils when the vapor pressure (water molecules breaking apart) in the water is equal to the pressure exerted on the water by the surrounding atmosphere. At sea level the pressure is approximately 14.7 psi (pounds per square inch).

I like to think of it this way. There are 212 balls pressing down on the water surface at sea level, so when the water heats to 212° F the water molecules fall apart and vaporize to squeeze by those 212 balls that are holding them down.

At 2,000 feet above sea level, the atmospheric pressure is less and there are only 208 balls pressing down on the water surface. So when the water reaches 208° F the molecules start to fall apart and vaporize.

At 4,000 feet above sea level, the atmospheric pressure is even less and there are only 204 balls pressing down on the water surface. At this altitude, water only has to reach 204° F for the molecules to fall apart and vaporize.

At 10,000 feet above sea level there are only 193 balls pressing down on the water surface. So, water is going to boil at 193° F.

Since food is cooked by the temperature of the boiling water, foods cook faster in boiling water at sea level than they do at 2,000, 4,000 or 10,000 feet above sea level. So even if the water is boiling at 10,000 feet above sea level, the temperature is still only 193° F and therefore food will take longer to cook.

How does this translate to cooking?

We are specifically talking about moist cooking environments, like boiling, steaming or braising; not baking or roasting.

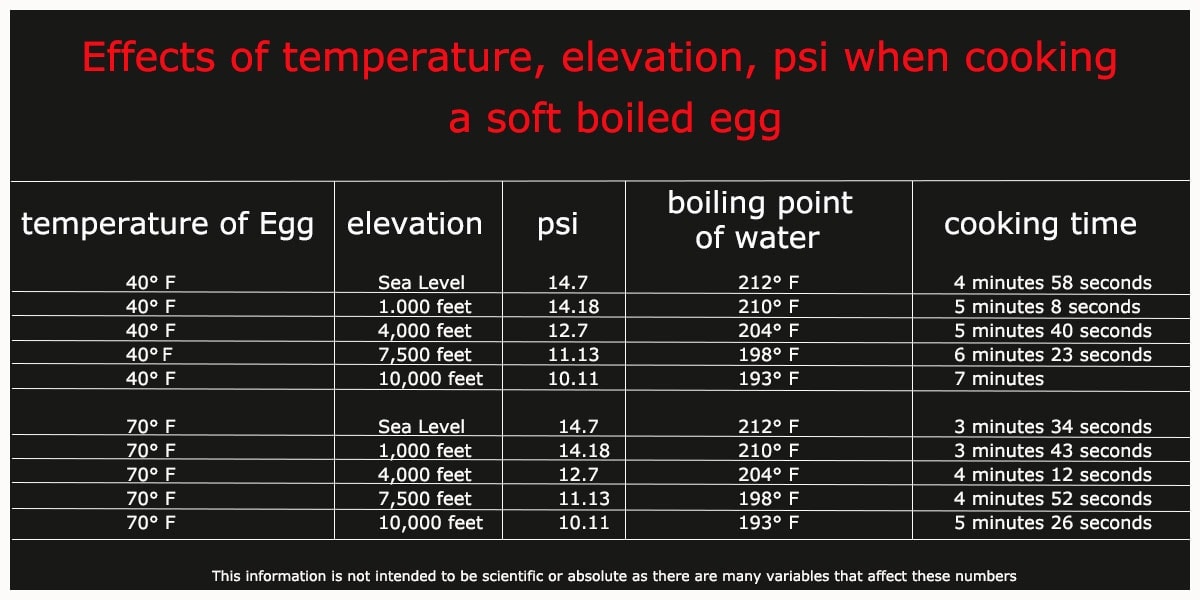

Let's use the example of a soft boiled egg. An egg boiled at 212° F will take less time to reach the soft boiled stage than an egg boiled at 193° F because it is the temperature that determines cooking time. Here is a chart that shows the various cooking times for a soft boiled egg at various elevations. * I used information from this website to create the chart.

So, now you can see how food temperature and pressure affect the cooking times of a soft boiled egg. The principle is the same for all foods. Now let's get into how cooking with a pressure cooker changes temperatures and cook time.

Principle Three: How a Pressure Cooker Cooks Food

The most important concept to understand when pressure cooking is that you are cooking food in a wet environment. The pressure cooker is either boiling, braising, or steaming (without evaporation) your food. That is why certain foods do very well in a pressure cooker and others might not fare so well.

Here is where all that mumbo jumbo about the boiling point of water come into play. I promise it is all about to make sense. So, remember how at sea level water boiled at 212 because there were 212 balls pressing down on the water surface. Well the pressure cooker increases those balls significantly. Remember when I talked about sea level being 14.7 psi and at sea level water boils at 212° F because it is at this point that vapor pressure of the water is equal to the atmospheric pressure? I know... I know... get to the point already. I promise I am.

Using the principles we just learned about how elevation and decreased psi lowers the boiling point of water, let's apply this to the pressure cooker. Think about it like you are cooking below sea level and the psi is greater below sea level, so the boiling point of water is increased. Let's say there are 243 balls pressing down on the surface of the water, then the water has to heat to 243° F before they break apart and make their way to the surface. This is the principle behind pressure cooking. The water or liquid is able to reach super-heated temperatures before it boils and therefore cooks your food faster. Instead of cooking at a boiling temp of 212° F, you are cooking at a boiling point of around 243° F.

The Ninja Foodi has 2 pressure settings. High and low. High pressure is a psi of 11.6 and low pressure is a psi of 7.2. Wait a minute! That makes no sense, does it? We already know that a psi of 11.6 will cause water to boil at around 198° F, so that would increase the cooking time, right? Nope, because we also have to factor in the psi at your altitude.

So, my elevation in TN is 489 feet above sea level and I don't have to make adjustments when cooking because it is basically sea level. The psi at sea level is 14.7 and the Ninja Foodi on high pressure has a psi of 11.6. So we add the two together, 14.7 + 11.6 = 26.3 psi. The Ninja Foodi on high pressure is operating under a pressure of 26.3 psi to cook your food. This changes the boiling point of water to around 243° F.

If you want to see what the boiling point of water is at your elevation and atmospheric pressure, you can use this calculator from Thermoworks.

Just what is going on in that pressure cooker?

We know we are cooking at a higher psi in the pressure cooker and this, in turn, raises the boiling point of water. It is also important to understand that even though those water molecules are breaking apart and rising to the surface when the liquid in the pressure cooker boils, they don't have anywhere to go. They are trapped inside the sealed pot. This results in little to no evaporation of the liquid inside.

When you turn your pressure cooker on, set to pressure, and seal the valve, this is what happens. The pressure cooker heats the water, releasing some steam through the red float button and the black venting valve until it reaches the desired pressure (varies with types of pressure cookers and the setting). Then the vaporized water (steam) causes the float button (the red button on the Ninja Foodi) to pop up, essentially sealing the pot and trapping all that steam. The temperature in the pot stays around (this only an estimate based on my research) 235° F to 245° F on the high pressure setting and your food is cooked at this temperature for the amount of time you set.

The rule of thumb I use for cooking food under pressure is the ⅓ rule. I set the pressure cooker to ⅓ the amount of time it would take me to cook the same food on the stove or in the oven using a wet cooking technique; such as boiling, braising, or steaming. I start with looking up how long a food takes to cook on the stove/oven and decrease the time by ⅔rds. I will get into this in more detail later in the article

This is not exact and as I have mentioned before, there are way too many variables for anyone to create an exact cheat sheet for pressure cooking. Anytime you refer to a cheat sheet, use that as a guideline only and put these principles to use to choose your best cooking times. When in doubt, cook for a shorter length of time. You can always cook longer, but you can't uncook food.

Is that steam escaping from the valve/red button/lid normal?

Yes and No. It is completely normal to see some steam escaping from the red button or the black valve while the Ninja Foodi is coming up to pressure. I have even seen a tiny amount coming from around the lid that corrected itself and went under pressure just fine.

BUT, it is not normal to have steam pouring out from around the lid while it's coming up to pressure and is a sign that your silicone sealing ring is not installed properly or has some damage to it. Most of the time, you can just remove the lid and press the silicone ring back into place and continue on with pressure cooking. Use caution of course, the inside of the pot will be hot and steam has built up or you wouldn't be seeing it come out.

It is also not normal for steam to continue to escape from the red button or the black valve after the pot is under pressure. If this happens, cancel the cooking cycle and allow the pot to cool for a few minutes. Then release the pressure and remove the lid. If this keeps happening, you will want to call SharkNinja.

Different Methods of Cooking Food in a Pressure Cooker

Let's take a few minutes and talk about the different methods of cooking in under pressure.

Boiling

This is when you fully submerge your food in liquid inside of the pressure cooker. So, for example, if you place a whole chicken into the inner pot of the Ninja Foodi and cover it with water, once the Ninja Foodi comes up to high pressure, you are boiling your chicken at around 240° F. The result will be a chicken with pale, rubbery skin and it will fall apart into pieces.

Although that doesn't sound appetizing, it is the perfect way to cook a whole chicken quickly and retain the moisture in the meat. It is best used for chicken salad and soups or as shredded chicken to add to various recipes. The juices that are released from the chicken make for a basic chicken broth. If you add carrots, onions, and herbs to the water, your broth will be more flavorful. Once you remove the meat from the chicken, you can also follow this recipe for Instant Pot Bone Broth and make your own bone broth. It's terrific!

This is essentially what I am doing in this recipe for Ninja Foodi Spaghetti.

All the ingredients are submerged in the beef broth (except the tomato paste) and it is boiled for a very short time. This is also the method used for making soups.

Braising

Braising is when your food is cooked in a small amount of liquid, but not submerged. Usually you will sear the meat before braising to add flavor to the meat. This is a chemical reaction called the Malliard Reaction.

Braising in the pressure cooker is what most people do when making a pot roast, just like in this recipe for Pot Roast by the Pioneer Woman.

First you sear the seasoned meat in oil on the saute setting, then you deglaze the pan to remove any brown bits (called fond and full of flavor). Deglazing after sauteing is important before you cook under pressure because those little bits on the bottom can trigger the burn notice. Add in a bed of onions and place the roast on top. A minimal amount of liquid is used, just enough to bring the pot up to pressure. The meat itself is mostly being cooked by the steam and not the liquid.

Steaming

Steaming under pressure is when your food is raised completely above the liquid, not touching it at all. You use just enough liquid to bring the pot to pressure and create the steam. I mostly raise the food completely above the liquid when steaming hard boiled eggs, cooking with PIP (pot in pot) method, and steaming potatoes before using the TenderCrisp function to crisp them up. This also works for some seafood and veggies, but it is very easy to over cook delicate and quick cooking foods. While you can raise meats above the liquid line, you will want to read the next section before doing that so that you properly release the pressure and don't end up with a shriveled and dried up piece of meat.

PIP or Pot in Pot Method

Pot in pot cooking is when you utilize another container that holds your food and you set that container into the inner pot, whether on a rack or in the basket and sometimes even directly into the inner pot instead of placing the food directly into the inner pot.

With this method, you always put some liquid (usually water) in the bottom of the inner pot, so that steam can build up and allow the pot to pressurize. You do not have to add any additional liquid to the container that you are putting into the inner pot.

When you do this, you are able to better control the amount of water in your food as well as insulate the food from rapid boiling. You are in essence, steaming the food under pressure. You have to do this with any baked goods and it is also beneficial when making different components of a meal.

An example would be this apple cake with caramel icing. I still get excited when I see a picture of this cake! It is so hard to believe that it was cooked under pressure in the Ninja Foodi.

This is a two layer cake and I used 2 8" cake pans that were sitting on top of each other (both covered) and I placed them into the Ninaj Foodi on 1" pressure safe trivet. I added water to the inner pot to bring it up to pressure. This is pot in pot cooking.

Another example is when you put rice and water in a pressure safe dish (covered) and place it on a rack with water in the bottom of the inner pot so it will come to pressure and you could be cooking something else, like some chicken thighs in the bottom of the pot..

There are many benefits for cooking food this way and it can really can take your pressure cooking to a new level. Using this technique, you can also cook food in stages. For example; you could place a container that has wild rice and water in it and set the timer for 20-25 minutes, IR the pressure and add in a second container that has seasoned chicken breasts and cook the chicken breasts for the remaining 5-10 minutes that the rice has left to cook. Add in a veggie that takes the same time as the chicken and you have a complete meal with different cook times done at the same time!

I have been working on several recipes that use PIP method of cooking in the pressure cooker and I can't wait to share them with you all. There is so much to talk about with PIP cooking, I have decided that this subject is best suited for its own article. I will get that one out as soon as I can.

Until then, play around with it and let me know your successes and even your failures. That is how we all learn.

Principle Four: When to use Immediate Release Versus Natural Release

Here we go! I already know I am going to get a lot of feedback on this topic as it is wildly debated in every pressure cooking forum I've seen. As always, do what works for you and yields the best results for you. Here are my thought processes and reasoning behind choosing IR or NR or a combo of the two when I develop recipes.

Immediate Release (IR) when Pressure Cooking

First, let's better understand what is happening inside the pot when you immediately release the pressure after the cooking time is up. You are immediately allowing all the steam (water vapor) to escape and by doing this you reduce the pressure in the pot very quickly.

We already know that the higher the pressure (psi), the higher the boiling point of liquid is, so by immediately releasing the pressure you are lowering the pressure (psi) in the pot and decreasing the boiling point. The molecules of the liquid break apart and form vapor (steam) when the pressure is equal to or less than the temperature of the liquid.

So, by immediately releasing the pressure in the pot, you are lowering the boiling point of the liquid. Remember those balls we talked about early and how they are putting pressure on the surface of the water? Think of immediate release in pressure cooking as removing half of those balls, yet the liquid is still super-heated. Now we have a liquid temperature much greater than the pressure around it and those liquid molecules are breaking apart, turning to vapor and evaporating very quickly.

This also happens to the moisture in the food you are cooking. Let's use a whole chicken as an example. You have just pressure cooked a whole chicken for 15 minutes and you immediate release the pressure. The juices in the chicken are very hot due to the high cooking temperatures in the pressure cooker. When the pressure drops quickly, those juices evaporate and leave you with a dry tasting chicken. Another thing that can happen is your chicken falls apart due to the quick decrease in the pressure.

This same principle can be applied to all foods cooked in the pressure cooker, with the exception of foods completely submerged in liquid. Even when you IR and drop the pressure quickly, if your food is completely submerged in liquid, the liquid will stay hot enough to not cause a sudden evaporation. Some of the liquid may evaporate from the surface, but the food submerged will not be affected.

When to Immediately Release the Pressure

When cooking vegetables under pressure, you want to stop the cooking process as quickly as possible so I recommend the immediate release.

When you are making soups or liquidy meals and you want some evaporation to happen, use immediate release. One thing I will mention about this is, if your pot is very full or if you are cooking starchy foods, you may get a mixture of steam and liquid from the pot spurting out.

This happens because we are rapidly decreasing the pressure in the pot, thereby decreasing the boiling point and this puts the liquid into a full-on rapid boil (all those steam bubbles trying to escape) and they have no where to go but up through the pressure valve. I usually do a short natural release of just a few minutes to allow the pot to settle down. I have also been successful with a pulse release, which means I open the pressure release valve for a second or two and close it again. I wait a minute or two and repeat. I do this 3-4 times and then open the valve all the way.

When you aren't concerned about foods drying out, like with potatoes, you can immediately release the pressure. I have not had any issue with the rapid decrease in pressure causing potatoes to break apart. I believe this is due to the starchy content in potatoes that reduces the amount of evaporation.

When your meat/or other food is completely submerged in liquid. We talked about this earlier, but just to recap. When your food is completely submerged in liquid, it is fine to do an immediate release because the food will not be affected by the rapid decrease in pressure. Even when you immediate release a pot with a lot of liquid, you are not increasing or decreasing the temperature of the liquid, you are only decreasing the boiling point, so that few seconds of rapid boiling isn't affecting your food.

You can also use an immediate release with certain cuts of meats that are not affected as much by drying out. An example of this is my recipe for Ninja Foodi Chicken & Wild Rice with Carrots. Chicken thighs are a perfect example because they are so forgiving and can handle an immediate release without drying out. Although I have not tested this yet, I also believe fattier cuts of meat that have not undergone long pressure cooking times (like spare ribs or short ribs) can probably handle an immediate release, except for getting food out of the pot quicker there isn't a huge benefit to do this because these fattier cuts of meat will not over cook with a natural release.

Also keep in mind that food does not stop cooking just because you release the pressure. The residual heat will continue cooking food even after the pressure is released. You can remove the pot from the Ninja Foodi or pressure cooker to reduce the extra cooking or even plunge the pot into cold water if you really want that food to stop cooking fast.

When to Allow the Pot to Naturally Release its Pressure

A full natural release can take anywhere from just a few minutes to over 30 minutes depending on what is in the pot and how full it is. I recently made a bone broth with the max amount of liquid (which I do not recommend because it was a disaster - I forgot to account for the added liquid produced by the chicken parts and veggies and almost had an overflowing pot!) and it took about 45 minutes for the pressure to naturally release.

When you allow the pot to naturally release its pressure, there aren't any rapid changes in pressure that can cause a quick evaporation of steam. This keeps the juices in the food where they belong, which is super important when pressure cooking lean meats like chicken, certain cuts of pork and some cuts of beef.

Something to keep in mind when allowing your pressure cooker to naturally release its pressure: food is still cooking during this process. The temperature drop inside the pot is not that much, so this should be factored in to your total cooking time.

A little sidebar comment here: I also factor in some of the time the pot takes to come up to pressure when deciding on a cooking time for pressure cooking. My rule of thumb is; I count ¼ of the time it takes to come to pressure as cooking time. So, if a piece of pork will take 6 minutes under pressure to cook and it took 8 minutes to come up to pressure, I will adjust the time to 4 minutes of high pressure.

When to do Natural Release followed by a Quick Release

This is the most common form of releasing pressure found in most recipes. They will tell you to natural release for 5 or 10 minutes, followed by a quick release of any remaining pressure. In my opinion, this is the best way to hand pressure releasing of most foods.

The two exceptions that come to mind are quick cooking foods, like veggies or seafood (although I don't recommend pressure cooking seafood or quick cooking veggies) and foods that will not be affected by longer cook times as much as they are affected by rapid evaporation; like pot roasts.

When you allow the pressure cooker to naturally release some of its pressure, it will maintain a slow decrease in pressure and not cause that quick evaporation in foods. This is a great technique to use when cooking chicken breasts that can dry out easily and become hard.

Again, you should factor in the time of the natural release as cooking time because your food is still cooking. This is why I always recommend setting the pressure cooking time for less time rather than more if you are unsure of an exact time. You can always cook it longer if needed.

One of the best things about the Ninja Foodi is the ability to switch from pressure cooking and other modes of cooking quickly and easily. You don't always have to put your food back under pressure if your food isn't done. Take chicken breasts for example; let's say that your chicken is completely done after you pressure cooked it and natural released for a few minutes. Put the pressure cooking lid on with the black valve to vent and steam it for a few minutes. The beauty of steaming with the Ninja Foodi is that you can lift the lid at any time to check on your food.

What about that Keep Warm Button?

Let's quickly address that keep warm button. Should it be left on or should it be left off? That is the question. I must confess that I was wrong about this and didn't realize it until I was writing this article. I thought that by turning the keep the warm button off, you would prevent food from over cooking and speed up the natural release of pressure. I was wrong and the reasoning behind it makes total sense.

The keep warm button is intended to do just that; keep your food warm. Based on food safety guidelines a safe holding temperature for food is 140° F. At this temperature bacteria does not multiply as quickly and keeps food safe to eat. So, although I can't find the documentation on this, I have to assume that the keep warm function will keep your food at at least 140° F and probably won't heat it past 165º F.

We already know that the temperature in the pressure cooker is way higher than 140º F and the liquid/food doesn't drop in temperature that quickly during any form of pressure release. So, based on this information, the keep warm button will not do anything to your food unless the temperature in your pot drops below 140º F.

Since the temperature in your pot doesn't drop to 140º F until way after any type of pressure release happens, the keep warm button can be left on and will not affect anything.

The one exception is leaving it on with food in it for extended periods of time. Soups and stews are probably fine, but pasta dishes and other meat dishes can overcook and dry out even at the low temp of 140º F.

Should I use Low or High Pressure?

I wanted to address this real quick, but I honestly have not used the low pressure setting enough to go into any great detail. I will work on that and update the article as I learn more.

The low pressure of the Ninja Foodi has a psi of 7.2, so at sea level the Ninja Foodi (if you are using a different pressure cooker, you will have to check that brand for its settings) is operating at a psi of 21.9. This means that the boiling point of water is about 238° F. That is about 5º F less than operating at high pressure.

We know that the lower the pressure, the lower the boiling point and the lower the boiling point the longer it takes for food to cook. So, food will take longer on the low setting, but I bet that isn't all there is to it. Does that pressure change affect the texture of food? This, I don't know... yet. I will be working on some testing to see if there is any advantage to using the low pressure setting. If anyone has any thoughts on this, I'd love to hear them!

Principle Five: Choosing the right type of liquid

In this section we are going to pull from the previous information about the boiling point of water. Oh, no... not that again! I'm afraid so. The good news is you have already gone through the tough part, so this will be super easy to understand.

A quick review: The boiling point of water at sea level (14.7 psi) is 212° F and that number increases as we increase the psi. The pressure cooker increases the psi, so the boiling point of water is higher. This results in higher cooking temperatures. It is the steam produced by the boiling liquid that creates increased pressure, which in turn, triggers the red button on the Ninja Foodi to pop up and seal the pressure in. Without the steam being able to escape to the surface, we won't be able to come up to pressure. Okay? Okay.

What liquid can I use when Pressure Cooking?

For our purposes, we can substitute almost any thin liquid for water and be able to follow the same basic theory of boiling point and pressure. This means that you can use any kind of broth, clear juice, wine, or beer as a substitute for water and although it may take longer to come to pressure, these liquids will produce enough steam to allow the pressure cooker to come to pressure.

Can I use milk as the liquid? It's a thin liquid, right? Well, yes, it is a thin liquid, but it is made up of a mixture of water, fats, & proteins and this causes a few problems. Steam is needed for a pressure cooker to come up to pressure and the proteins and fats settle on the top of milk (you might have seen this layer when boiling milk on the stove) as it reaches it's boiling temp preventing the steam from being released, which in turns prevents pressure from building inside the pot. I am not saying that milk won't allow the pot to come to pressure (I honestly haven't tested it), but I am pretty sure that by the time enough steam is built up to come under pressure, the milk on the bottom will scorch due to the high heat. This would probably result in the burn notice. One last thing (at least that I know of), is milk separates at high pressure temperatures and curdles. While it's safe to eat, it isn't very appetizing, so I stay away from using milk when cooking under pressure.

I have had success in using evaporated milk as part of the liquid in recipes, but there is always another thin liquid in addition to the evaporated milk. I will be sure to do more experiments with milk and milk products and update this article accordingly.

Tips for making creamy or cheese-based sauces

If you want to make a creamy Alfredo sauce, use chicken stock as the liquid and a block of cream cheese on the top of the pasta (don't stir). When the pressure cook is complete, add a bit of heavy cream or milk along with freshly grated Parmesan cheese and stir to combine. The residual heat will warm the cream and melt the Parmesan cheese.

While I have not created the perfect Mac & Cheese recipe yet, I've come close! I want a creamy mac & cheese that uses non-processed cheese and this proving to be a little more difficult that I thought. Any suggestions? I would love to hear from you!

Here are a couple of things I've learned through trial and mostly error. Don't add in non-processed cheese before pressure cooking; it separates, looks horrible and does not blend well. Don't add baking soda to the water. You may think I'm crazy for mentioning this, but there is a recipe that calls for baking soda. I was so curious, I looked up why they would add it.

Turns out that baking soda can be used to keep the noodles crisper (al dente) during pressure cooking... okay, I like al dente pasta. I already knew that some Asian dishes use this to keep their shrimp firm, so I thought... okay, I'll give it a whirl. Right in the trash it went! I can't even begin to describe the horrid taste - I still have nightmares. All I can say, is I have eaten a lot of things in my life and can usually tolerate different flavors and textures even if I don't like them. This one, not so much.

What about tomato sauce?

I'm afraid you will run into the same issue here as with the milk. The viscosity (thickness) of most tomato based sauces is going to prevent the steam from escaping to build pressure before it scorches. Basically what is happening inside the pot with just tomato sauce, is the sauce is being heated and steam is being produced in the form of all those little bubbles, but they can't break free and get through the sauce until they reach a certain temp and, by then, you probably will get that darn burn notice.

It's the same principle as when you heat tomato sauce on the stove. You start off on a low heat, nothing is happening, so you turn up the heat and all of a sudden you have tomato sauce all over your stove and maybe even your ceiling because the sauce finally got hot enough to let all those little steam bubbles escape and your sauce erupted under the higher heat and may have even scorched on the bottom.

You can use tomato sauce while pressure cooking, but you need to dilute it with a thin liquid like I do in this recipe for Ninja Foodi Spaghetti. To make up for the dilution, try adding tomato paste on top (don't stir) and then stir to combine after the pressure cook time is finished. Remember to add a bit more spice to make up for the tomato paste or your sauce might be bland.

Are there other liquids you want to use while pressure cooking and aren't sure if they will work? Leave a comment at the end of this article and I'll be sure to help you out! You can also join our Facebook Group Ninja Foodi 101 and ask the question there. We have a great group of people that are always willing to help you out!

Should I use hot liquid or cold liquid?

The short answer is, it doesn't really matter. Both hot and cold thin liquid will allow your pressure cooker to come up to pressure. The difference is the time it takes to heat up, create those water vapor bubbles that escape from the surface and produce sufficient steam to seal the pot.

Adding hot liquid will speed up the process slightly, some people even put the Ninja Foodi on the saute mode and get the liquid boiling before closing the lid. I don't really see the point in that, for me it's just an extra step and the liquid heats faster when you put the lid on and seal the valve because the heat is not escaping, just like a covered pot comes to a boil quicker.

The Ninja Foodi does a great job at heating the liquid quickly, so I usually don't bother with heating the liquid. What I do recommend is once you make a recipe, especially something that has a short cook time like white rice, do it the same way each time. So, if you heated your water (or any liquid) before making rice and it was perfect for you, do that all the time.

Principle Six: Choosing the right amount of liquid

Originally I had combined this topic with the previous one about choosing the right kind of liquid, but there really is a lot that goes into choosing the right amount and I think it requires it's own section.

How do I know how much liquid to add when Pressure Cooking?

This is something I put a lot of thought into when developing a recipe and there are many variables to determining the right amount of liquid. I am going to go over as many as I can think of, but if you still have questions, don't hesitate to ask. Leave a comment at the end and I will definitely get back to you.

The basic rule of thumb I use is to use the least amount of liquid needed to come to pressure and meet the requirements of the food I am cooking. The Ninja Foodi recommends at least ½ cup of liquid in the 6.5 quart and the 8.5 quart. .

Things to consider when choosing the amount of liquid to use.

Do I want my food to be submerged in liquid for cooking? There are a few instances where you might want to submerge your food, like to boil a chicken. Or perhaps you want to boil corned beef. In these instances, place your food in the inner pot and fill with liquid until the food is covered. Just make sure you do not go over the max fill line that is marked on the inside of the inner pot and sometimes it is best to stay a few cups under that line (see below).

Another thing to consider is how much liquid will the food give off during the pressure cooking process. I recently made the mistake of not taking that into consideration when making bone broth. Even though most of the meat was removed from the previously cooked chicken, there still was skin and cartilage that broke down during the pressure cooking process and created extra liquid. My pot was so full at the end of the pressure cooking time, I am surprised it didn't overflow.

Do I want to have a concentrated liquid at the end of pressure cooking in order to make a sauce? Let's use a chuck roast as an example. Is your goal to have a rich concentrated sauce with which to make gravy? If that is the case, I would not add more than one cup of liquid (my choice would be beef broth). The chuck roast will give off its own liquid as the fat breaks down during pressure cooking and you will end up with 2-3 cups of liquid with which to make gravy.

Quick Tip: Make sure to add extra seasoning to the liquid you use. For a chuck roast I usually add fresh herbs like Rosemary and Thyme as well as cut-up onions, some whole garlic cloves and a bay leaf. I remove these from the liquid before adding flour to make the gravy. If you want to see how I make gravy in the Ninja Foodi, you can check out this video for sausage gravy. The principles are the same for a pot roast. Sift your flour on top and allow the flour to absorb the fat before stirring.

Do I want my food to absorb all or most of the liquid? This would be the case with rice. Who wants wet rice? Not me. There are a few things to consider when making rice. Always keep in mind that there is little to no evaporation when cooking under pressure, so your rice to liquid ratios will be different than when cooking stove top or even in a rice cooker.

I recommend always allowing your rice to natural release for at least 5 minutes before releasing the pressure and this is why: if you set the cook time long enough for the rice to absorb all of the liquid, you will have a dry pot and a dry pot of rice will give you the burn notice pretty quickly. Always assume that there is some liquid left and you want the rice to absorb it after the pressure cooking cycle is complete to avoid that burn notice.

I wish I could provide you with a good guideline on water to rice ratio and the various cooking times, but the truth is I just haven't had consistent enough results with cooking rice by itself. I am working on it though and will update article when my testing is complete. I have had better luck using the steam function for rice with the PIP (pot in pot) method, but still working on exact timing for that too.

When making a food, like rice or pasta, along with other foods at the same time, you also want to take into consideration what liquid those other foods will give off and decrease your thin liquid accordingly. For example; when I made this Chicken & Wild Rice with Carrots complete dinner in the Ninja Foodi. I decreased my liquid to 2 cups instead of 2.5 cups that I would have probably added had I of just been cooking wild rice. I knew the chicken thighs would give off liquid and I approximated that to be about ½ cup.

That wraps up the basic principles of pressure cooking, I hope you have a better understanding of how the pressure cooker and works and your food is being cooked.

I know all this research helped me a lot. If you have questions be sure to leave a comment or shoot me an email. I am happy to help in any way I can.

Now, let's delve into some frequently asked questions about pressure cooking.

Do I have to make adjustments for High Altitudes?

If you live at an altitude of 3,000 or more feet above sea level, you are cooking at a high altitude and adjustments need to be made, even in a pressure cooker.

I have heard people say that the pressure cooker equalizes cooking for everyone and therefore adjustments don't have to be made. Unfortunately, this is not true and it goes back to Principle One and Principle Two in this article.

Even at 2,000 feet above sea level the boiling point of water drops to 208° F, but for most cooking applications this will not make a significant difference in time.

At 3,000 feet above sea level (approx 13.2 psi), the boiling point of water is 206° F and adjustments need to be made to the cooking time of foods in the pressure cooker.

The PSI of the pressure cooker remains the same, but the psi of the atmosphere surrounding it is lower. So, now instead of cooking with a psi of 26.3, you are cooking at a psi of 24.8 and the boiling point of water at that pressure is around 239. That might not seem like a huge difference and it isn't really. Sort of like setting your oven to 325° F instead of 350º F. It does however alter your cooking time a bit.

The rule of thumb when pressure cooking at high altitude is to increase the pressure cooking time by 5% for every 1,000 feet above 2,000 feet. Let's use my recipe for Instant Pot Whole Chicken as an example.

The recipe states to cook a whole chicken for 4 minutes per pound and let's say we have a 5 pound chicken. The cooking times would like like this:

- Sea Level: 20 minutes of high pressure cooking

- 2,000 feet above sea level: 20 minutes of high pressure cooking

- 3,000 feet above sea level: 21 minutes of high pressure cooking (20 min x 1.05 = 21)

- 4,000 feet above sea level: 22 minutes of high pressure cooking (20 min x 1.10 = 22)

- 5,000 feet above sea level: 23 minutes of high pressure cooking (20 min x 1.15 = 23)

- 6,000 feet above sea level: 24 minutes of high pressure cooking (20 min x 1.20 = 24)

- 7,000 feet above sea level: 25 minutes of high pressure cooking (20 min x 1.25 = 25)

That was pretty straight forward. Now, let's look at a recipe that takes less time to cook and see what that looks like. I just made these Chocolate Cake Bites the other day, so lets look at that recipe.

The recipe calls for the cake bites to be cooked in the silicone mold for 6 minutes with a 4 minute natural release, followed by manually releasing the remaining pressure. This is what the cooking times would look like.

- Sea Level: 6 minutes under high pressure

- 2,000 feet above sea level: 6 minutes under high pressure

- 3,000 feet above sea level: 6 minutes and 18 seconds under high pressure

- 4,000 feet above sea level: 6 minutes and 36 seconds under high pressure

- 5,000 feet above sea level: 6 minutes and 54 seconds under high pressure

- 6,000 feet above sea level: 7 minutes and 12 seconds under high pressure

- 7,000 feet above sea level: 7 minutes and 30 seconds under high pressure

Oh boy! You can't set pressure cookers for less than a minute, so what do we do with this recipe at high altitudes? This is where we use the information in Pressure Cooking 101 and get a little creative.

So, for this recipe at 3,000 feet, I probably would not make any adjustments. I don't think 18 seconds is going to matter either way.

At 4,000 feet, I would increase the natural release time by 1 minutes. So, cook on high pressure for 6 minutes and natural release for 5 minutes. Since food continues to cook during the natural release, but at a lower temp, I think this will do the trick.

At 5,000 feet, I would increase the pressure cook time to 7 minutes. That was an easy one.

At 6,000 feet, I would pressure cook for 7 minutes and leave the release time alone.

At 7,000 feet, what would you do? Leave me a comment!

I may add to this section or do a separate article on high altitude cooking because it is super interesting and from what I've read, there are some ingredient adjustments that need to be made too. For now, I hope this helps a bit with calculating time adjustments when cooking at altitude.

How do I know what containers are safe to use?

I certainly am no expert on this subject, but I have done enough reading that I feel very comfortable in giving you some tips and recommendations.

Can I use Glass in a Pressure Cooker?

At one point it was assumed by many people (including me) that any oven-safe dishware would be safe in a pressure cooker and I have to confess that I have used all kinds of oven-safe dishware without incident; however, that doesn't mean it was the right thing to use for more reasons than you might think!

Corelle Brands, the makers of Pyrex® has come out and said that is NOT recommended that their containers to be used for pressure cooking. These containers are not designed for pressure cooking and could crack or explode under pressure.

You might say, I'll chance it... and you certainly have that right, but you might want to consider this first: glass does not conduct heat as well as aluminum does, so your food is going to take longer to cook. Isn't the idea of the pressure cooker to speed things up?

The same is true of ceramic and I know this for sure because while I was developing this recipe for Apple Cake with Caramel Icing, I was using a ceramic casserole dish. Every single time I tried to make this cake, I couldn't get the texture of the cake right. It was always a little underdone and I'm talking after 60 minutes of pressure cooking. Then I switched to these 8" Fat Daddio aluminum pans and not only did I get the cake to cook perfectly, it was done in 30 minutes. That's how much of a difference it made in this instance.

I plan on doing more research on this topic and reach out to different brands to find out if there any glass or ceramic containers that are safely recommended and I will update this article as more information is available.

I have found that I can usually find another container to suit my pressure cooking needs. For example, I want to make crème brûlée in the Ninja Foodi, but what do I do if I can't use my cute Ramekins? I can use these adorable mason jars instead!

One last thing I do want to mention is: if you do (and I am NOT suggesting that you do) use a heavy glass or ceramic dish, be sure to allow the temperature of glass to decrease slowly. What I mean by that is; don't take it steaming hot out of the pressure cooker and place it on a cold counter. It make break into a thousand pieces. Also, don't put it in or on a surface with water. The water will conduct heat away quickly from the glass and it could break into... yep, you got it, a thousand pieces.

What about Silicone? Is that safe?

Yep, as long as it is food grade silicone, it is fine to use in the pressure cooker with one caveat: it doesn't conduct heat well, so you may have to adjust your cooking times.

Let' say a recipe calls for a meatloaf to be cooked in an aluminum foil in the pressure cooker and you just happen to have a silicone meatloaf pan and decide to use it. If the recipe calls for a pressure cooking time of 25 minutes, you will have to increase that time to compensate for the silicone loaf pan. By how much? I don't know, because I haven't done it. I would probably add at least 5 or 10 minutes; but I'm just guessing here, friends.

Some of my favorite Silicone products are:

Silicone Egg Bite Mold: I know this sound crazy, but I haven't used them yet for egg bites. I fell in love with these because they are the perfect size to make this recipe for Chocolate Cake Bites!

Grifiti Bands: I use these all the time to put around pans to easily lift food in and out of the Ninja Foodi.

Silicone Chef's Basting Brush: Although this doesn't go into the Ninja Foodi, I thought it was worth mentioning because it is one of the most used kitchen item, besides the Foodi of course!

Silicone Finger Mitts: I use these all the time to lift out the hot pot, rack, and basket. I like them better than a full glove.

Cooking with Aluminum:

Aluminum is a great conductor of heat and works perfectly in the pressure cooker. It heats quickly, cools quickly, and most importantly (to me anyway) can go straight from pressure cooking to Air Crisping without any concerns.

I have been using a 7" Spring from pan from Pampered Chef that I like a lot. I started testing a Mint Cheesecake in it and was very impressed with how it turned out. The crust was even crisp.

Aluminum has also come under some debate as to if it safe or not to use while cooking. Since I recommend Fat Daddio's cake pans all the time, I decided to read up on this topic a bit.

Instead of reinventing the wheel here, I found an article that I found to be very informative. So, if you want to, give it a read.

What Everyone Needs to Know About Aluminum Cookware

Are there foods I can't cook in a Pressure Cooker?

You CAN cook any food in a pressure cooker. The real question is SHOULD you cook all foods in a pressure cooker. My opinion is, no. All foods do not do well in a pressure cooker.

I am not going to be the one to tell you what to cook or not cook in your pressure cooker because everyone has different tastes when it comes to food. What I will share with you is my thought process when deciding if I want to pressure cook a certain food.

These are the questions I ask myself:

- Does it take less than 5 minutes to cook on the stove? If the answer is yes, I don't pressure cook it. There are a few exceptions to this and the one that comes to mind is a poached egg. Although I have yet to get the timing exactly right, I can see the advantages of using the pressure cooker over the stove.

- Is it expensive? If it is an expensive cut of meat or seafood and I don't know exactly how it will cook under pressure, I don't usually risk it. I say usually, because it's my job to experiment with food, so I do sometimes break this "rule".

- Will the texture be adversely effected by pressure cooking? Take broccoli for example; I wouldn't pressure cook broccoli because it would turn to mush. Now, I might pressure cook broccoli if I am making a broccoli soup. As a rule though, I would choose steam.

- Is this for a special occasion? I don't recommend pressure cooking any food that you haven't done before when cooking for a special occasion or a holiday dinner. Stick to what you know works and maybe give it a try in the pressure cooker another time. There is nothing that deters someone from cooking, more than a failed meal on a special occasion. Don't do that to yourself. I don't do it to myself.

- Is it a very thin cut of meat? Let's take steaks for example; if they are less than 1" thick (frozen or not), I don't recommend pressure cooking them. Same with thin pork chops. They just don't fair well in a pressure cooker. That's why I love the Ninja Foodi so much, you can bake or air crisp them in no time and they turn out wonderful.

Now, on to the most asked question of all!

How do I adapt a favorite recipe for the Pressure Cooker

Just by reading this (very lengthy, I know) article, you have already learned the principles needed to adapt a recipe for pressure cooking. I can see the heads shaking and the mouths saying, "No, I really haven't. I need more help."

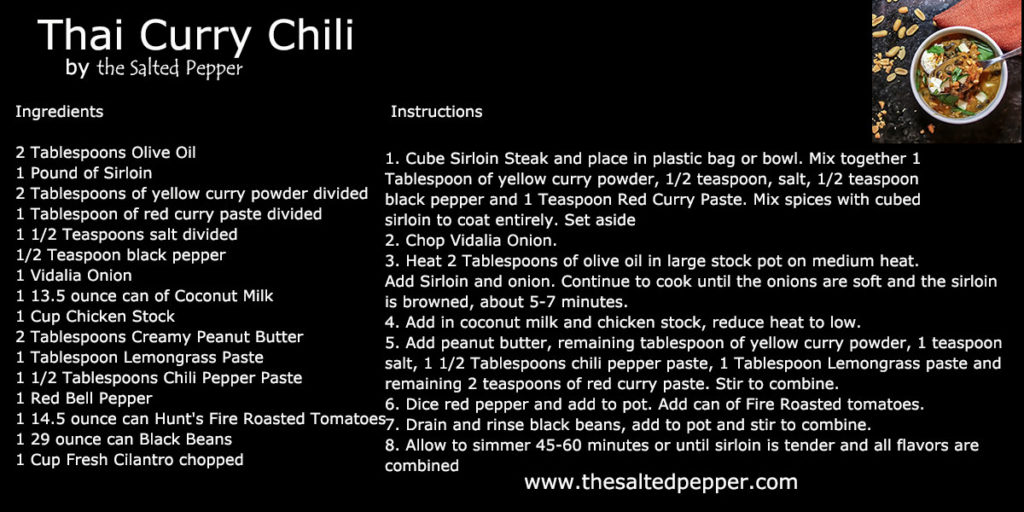

You will be surprised that those 6 principles of pressure cooking that we went over are the keys to adapting a recipe, but let's do one together so you see what I'm talking about. This recipe for Thai Curry Chili has won several chili cook-offs and is a personal favorite of mine. I developed the recipe for the stove top, but I'll bet we can convert it to the pressure cooker easily. Let's take a look at it.

The first thing you want to do is read through the ingredients and list those that might cause problems cooking under pressure. These would be foods that would make it hard for the steam to be created, because they are too thick.

The first one that I see is the coconut milk. I have never cooked under pressure with coconut milk, but I know how thick it is.

The second would be the peanut butter, but we can always put that on top like we do with cream cheese or tomato paste, so that one is fine.

The third ingredient that I would want to consider, but not because of coming up to pressure, is the black beans. They are already cooked. So, I would think about that and determine if I should add them during the pressure cooking time or after. In this case the risk of them turning to mush is greater than them not being heated all the way through, so I will add these after the pressure cook time. Now, I have pressure cooked canned beans before like in this recipe for Instant Pot Chili and they were fine, so I think this could go either way really.

Okay, so the only ingredient we really have to deal with is the coconut milk. Now, let's look at the instructions. When you review the instructions, start to think about how you would execute the instructions using the Ninja Foodi or pressure cooker.

So, in #3 of the instructions, it says to saute the onion and the sirloin. That's easily done in the Foodi, so no problem.

#4 of the instructions has that pesky (but important) coconut milk. Skip that for now. The chicken stock is fine, but look at the volume and consider if it is too much because we don't have evaporation in the pressure cooker. It's only 1 cup, so no this will not create a problem. If it said 4 cups, I would definitely be looking for key words, like reduce, further along in the instructions. If a recipe has "reduce" in the instructions, that means they want you to cook off some of the liquid. This is not going to be possible while cooking under pressure, so I would consider reducing the amount of liquid.

Everything else looks fine, so we check the cook time. This says to simmer for 45- 60 minutes. This will tenderize the sirloin and help combine all the flavors. Okay, so we know the rule of thumb is to cook ⅓ of the stated time. That would be 15 minutes. Does that sound logical? I think so.

So the only thing left is that coconut milk. Could we pour it on top? Or mix it with the peanut butter and then pour it on top? What do we know about milk and pressure cooking? It curdles. Will coconut milk do that? I'm not sure, but I can google it.

Sure enough, the first thing that pops up is about milk curdling and that includes coconut milk. Okay, no problem. We will leave it out until after the cooking is complete. Now we have the beans and the coconut milk that we will add after the pressure cooking time is up. Simple enough.

Let's think about what is already in the pot. We have the sirloin, the onions, the chicken stock, the spices (which might be thick too), the tomatoes and the bell pepper. Imagine what that looks like in your mind and start to estimate how much liquid these ingredients will give off.

We sautéed the onions and the sirloin in oil, so there is ½ cup of liquid probably. We have the juice from the tomatoes, that is probably ¼ cup. The red peppers will give off some liquid, maybe an ⅛ of a cup and we have the chicken stock. I'm feeling pretty good about this.

My plan will be to season and sauté the sirloin with the onions as the directions state. Then, add the chicken stock and the diced tomatoes. Next, I put in the red peppers and the spices and give it a stir. Does it look too thick? If so, add a little more chicken stock; if not. keep going. I would put the peanut butter on top, but not stir. I could also leave it out and add it when I add the other two ingredients, but I'm pretty confident that it will sit on top and not cause any trouble and, by pressure cooking it, it will be easier to incorporate when I do stir because it is hot already.

We determined that 15 minutes was the right amount of pressure cooking time earlier, do we need to make adjustments for that since we have left out 2 ingredients that would increase the volume in the pot? Yes, I think so, for two reasons. One, I always set times lower if I am not sure how long to cook. I can always cook longer, but I can't uncook. Two, I will probably simmer this for at least a few minutes to get those two ingredients incorporated after the pressure cooking time. I would set the pressure cook time for around 10-12 minutes.

Now, I have not made this in the pressure cooker before. I have never even thought about adapting this recipe for the pressure cooker until I got to this section. Am I 100% sure I'll be successful when I make this? No, I'm not. Do I think I have a pretty good chance of being successful? Yes, I do.

It doesn't take fancy cooking skills or any special training to be able to cook. The most important thing is wanting to try and not being afraid to fail sometimes. Lord knows, I have had complete dinner failures and I just use them as a learning experience.

In many ways, cooking under pressure is harder than stove top cooking because you can't really check on the food once it's in the pot. It is important to have an understanding of how the pressure cooker works and a basic understanding of how food cooks in a pressure cooker in order to be successful at it.

Remember, "While pressure cooking is easy, it isn't simple."

That is why I wanted to share with you all these principles of pressure cooking and a few tid bits of helpful (I hope anyway) information as well as some thought processes that I consider when creating or adapting recipes for the pressure cooker.

I wish you nothing but success! Happy Pressure Cooking!

All my best,

Louise

I really would love your feedback on this article. Please leave a comment below and tell me if you found it helpful or not.

You also might be interested in reading my other article: How to Use your Ninja Foodi ~ Volume One: Getting Started.

Anon

Waste of time. No information on meat

Louise

I think you have misunderstood what this article is about. It is about the basics of pressure cooking, not about specific foods to pressure cook. However, I am happy to help you if you want to email me the questions you have about pressure cooking meat. Each one is treated differently.